Scotland and the cost of living crisis

You can't eat progressive rhetoric, you can’t heat your home with a tastefully produced video, and you can’t pay your rent with the latest public relations photo-op

This crisis is not a flash in the pan

There can only be one topic this week: the cost of living. To begin, we need to get a sense of scale about the nature of this crisis. Coming after a decade of austerity and a pandemic, we are set to see the biggest fall in living standards in a single financial year since records began in the 1950s.

As we can see in the following chart, disposable income is going to plummet as prices rise, and as wages continue to stagnate, or fall.

Such a collapse is going to have major ramifications for the economy as a whole. Richard Murphy, Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University, outlines why we are heading towards a major economic crisis:

“As struggling households cut all their leisure spending back, or end it, the secondary reaction is going to kick in. That means large scale business closures, and then mass unemployment. The leisure, tourism and travel sectors are clearly going to be hardest hit by this. The ONS data shows that everyone who can likes going out in the UK. But that’s not going to happen with bills rising this much.

“There is going to be economic meltdown in these sectors. Once these secondary effects kick in so does the financial crisis as debts, rents, mortgages and utility bills, go unpaid. People without the money to pay their debts cannot settle them. The consequence is that a full-blown debt and banking crisis is on the cards.How big a crisis? Something that makes 2008 look like a picnic…”

I don’t agree with everything Richard says about economics (especially about Modern Monetary Theory, though that’s for another day), but I do agree with his assessment here. This is not a flash in the pan. We are looking at a protracted crisis, and one which overlaps onto a pre-existing context of cuts, privatisation and endemic poverty. This process is structured in to the system itself. As an Oxfam report into the cost of austerity and inequality reflected:

“The UK is the sixth richest country in the world.1 From 1993 to 2008 it saw 15 years of economic growth, underpinned by the socio-economic reforms of the 1980s. This shift towards market-based capitalism was characterised by financial liberalisation, the erosion of social security and deregulation of the labour market.

“However, these reforms have led to a dramatic increase in the number of people living in poverty, which almost doubled, from 7.3 million people in 1979 to 13.5 million in 2008, and inequality reached levels last seen in the 1920s, driven by a growing share of income going to the richest, in particular the top one per cent.”

With this in mind, let’s take a look at the forecasts for nominal and real average earnings. The graph on the left (below) shows the steep decline in average nominal earnings growth, followed by a very limited “recovery.” Except, it wouldn’t really be anything like a recovery, but an entrenched period of stagnation at a very low level. On the right, the real consumption wage collapses between now and the end of 2023. It only slightly recovers by 2027 and even then is lower than it is in 2021.

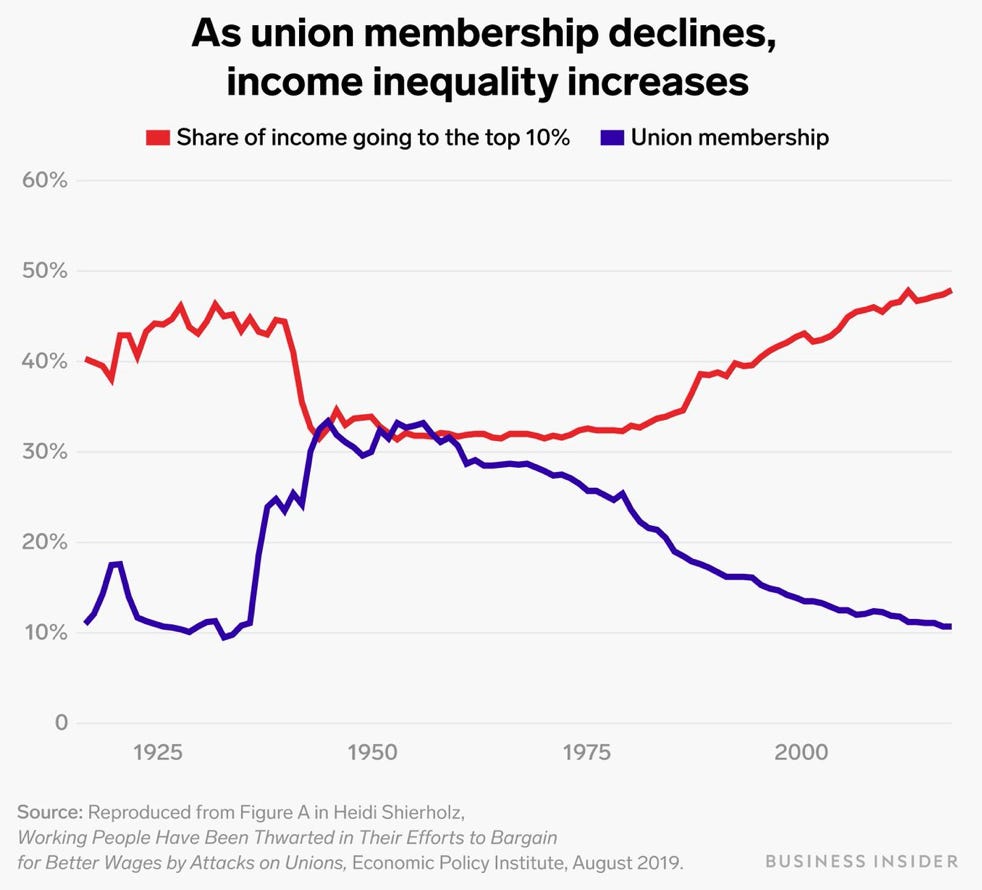

The truth is that only a highly organised resistance to this process will bring about any real change. This, of course, is nothing new. Indeed the massive upwards transfer of wealth and the attendant growing inequality this produces is only possible if the real wealth creators - the working class - are demobilised. The attacks on the trade union movement, in the form of the anti-union laws and as a result of major defeats such as the miners strike in the 1980s, have had a lasting impact.

Indeed, as union membership grew between the early part of the last century to the 1950s, the share of income going to the top 10% fell to its lowest ever level. The onset of neoliberalism in the late 1970s and the triumph of Thatcherism in the 1980s cemented the long decline of trade union membership. At the same time, the share of income to the top 10% grew and consolidated.

Just look at the behaviour of P&O ferries today and the anti-union practices which threaten to further erode the collective power of organised labour at a time of major economic upheaval.

As Tribune editor, Ronan Burtenshaw rightly concludes:

“If companies like P&O consciously break the law, the penalties are so pathetically weak that they can simply be priced in. If unions break the law to fight back, they will have their assets seized (like they did in 1988 P&O dispute). That's the rigged game behind our economy.”

Class warfare

It was fashionable to say that the “class war” was over at the high point of the New Labour project. Of course, it begged the question: who won? In truth, it never came to an end, as attempts to rationalise the excesses of the system met head on with reality. The Sunak statement, and the years of austerity, are acts of class war. Not just because they displace the cost of the economic crisis onto the working class and the poor, but because in the process wealth becomes further concentrated at the top of the system.

As the TUC reported in 2019:

“Working families have struggled to make ends meet since the 2008/10 survey due to the longest pay squeeze in two centuries and the impact of austerity on their earnings. But those at the top haven’t had to worry. Their wealth has grown by a whopping £2.6 trillion over the same period – three times as fast as those in the bottom 10 per cent.”

So it is no surprise that Sunak continues in this vein. His woeful response to the crisis shows how distant he is from the real world. Indeed, there are even those in ruling class circles who express a nervousness about the statement. Social peace is not a given in a situation like this, and after years of political volatility, some of the more strategic sections of the establishment understand the need for a partial, albeit limited, form of redistribution. For some liberal theorists, such as Francis Fukuyama, this is required to reinvigorate and protect democracy, shielding institutions from further political shocks in the process.

Speaking of volatility, a YouGov poll showed that just 6% of respondents thought that the plan did enough to confront the issues. Explosions await, as formal politics appears to have no answers about the way forward for tens of millions of people.

Sunak might have the sharp suit and the ability to string a sentence together (yes, the bench mark these days is really that low) but he doesn’t have much in the way of intellectual substance. No matter how much the Ruth Davidson wing of the Tory party try to paint him as natural leader, in touch with the people, he is evidently anything but. At a time where millions of people can’t afford basic necessities, that will count.

Yet this is about more than any individual. This is about a rigged system. Even the proposals made by rival political parties amount to little more than sticking plaster. Yes, we get the usual bluster: the Tories are bad and looking out for the rich. Who knew? But who, if anyone, is really prepared to challenge the failures of the economic system writ large? That is a far more difficult question, especially after the defeats of the more radical political tendencies around both Corbynism and the independence movement of 2014

The long crisis in Scotland

In the years that followed the 2008 crash, with the ensuing cuts, I was active in the various social movements against austerity. We fought against day care centre closures, organised solidarity for striking workers, and joined the student revolt. Around 2012, a shift took place in Scotland, contoured by these events, that would come to define the national politics of the country for many years to come.

In short, the possibility of independence became the lightening rod around which anti-austerity politics could find identity, organisation - and importantly - some kind of victory. The route out of cuts, and towards democratic control, was clear: independence from Westminster rule. The independence movement, organised from below by working class people the length and breadth of the country, signalled a break with Labour, and far exceeded the mobilising capacities of the trade union movement.

Huge sections of the Scottish working class not only voted Yes, but campaigned on the issue too. Every public meeting, every stall, every impassioned conversation had at is core an opposition to austerity, and the notion of real social transformation through independence.

It was not to be seen as a magic wand. But here at least, after losing the major class battles (barring the poll-tax) that defined the latter part of the 20th century, was hope.

De-radicalising the independence movement

As I have previously outlined, this mass movement was sidelined by the SNP leadership in favour of corporate interests. Indeed, the existing prospectus for independence is based on Osborne’s deficit reduction approach to economics. It would necessitate austerity and would extract wealth from the Scottish people only for it to be reconsolidated in the City.

This all lies in stark opposition to the demands of the movement of 2014. In a period of intractable economic crisis, there is a need for a serious plan, and a vision for how exactly independence might transform peoples lives for the better. That remains absent - and confused. Murray Foote, the SNP media advisor, made the following point in the aftermath of the Spring statement:

“If you are the poorest/most vulnerable, you have AGAIN been neglected by Westminster Government, which invariably ignores its duty to protect all citizens equally. Britain is governed to perpetuate obscene inequality. So much AGAIN for the mythical “broad shoulders of the union”.

I mean, sure, that’s true. But independence supporters can’t afford (literally) to settle for rhetoric. This is especially true when the rhetoric doesn’t even make sense on its own terms. As many of us have been warning for several years now, the present currency position is a huge trap. The SNP case for independence accepts the idea of the “broad shoulders” of the Union. It would sacrifice economic control to the UK financial institutions. That is literally the premise of Sterlingisation.

Maybe Murray knows this, maybe he doesn’t. The point is, there isn’t any real strategic thinking going on here. If the UK economy is broken, why seek to replicate it? The big questions around currency, borders and so on should have been bedding in for years now - ready for this moment.

Instead we have SNP figures recycling tired old arguments about the Tories on the one hand, and begging them for scraps on the other. They conclude interviews by saying “we don’t have the power do to anything,” while at the same time doing nothing to win said power.

That is a recipe for inaction on all fronts.

Paralysis breeds disbelief

A recent poll showed that 52% of respondents felt that discussions about an independence referendum should stop because of the cost of living crisis. That is interesting - and in my view damning - as it shows the weakness of the official case for independence, such as it exists. But dig in further and we find that 30% of 2014 Yes voters also agreed that the cost of living crisis was a legitimate reason to stop referendum discussions.

Be under no illusions, significant sections have gone cold on independence because the insurgent quality associated with 2014 has gone into stark retreat and because faith in the possibility of a) a referendum actually happening and b) a radical outcome to such an event, has subsided.

This doesn’t mean in the end these voters won’t vote for independence in some distant referendum. But it does mean that motivation and belief, two vital ingredients in politics, has been lost. To return to an on-going theme, this is not an overwhelming problem for the SNP leadership who have actively set out to defenestrate the political agency of the 2014 movement in the years since the last referendum.

That said, problems are beginning to mount. The SNP are not armed with a theory of crisis, so they are vulnerable to treading water, or simply collapsing behind prevailing tendencies in the British state, the European institutions or the White House, every time new a crisis emerges.

The result is stultified thinking and a timid approach to politics in general.

Scots need action now

You cant’t eat progressive rhetoric, you can’t heat your home with a tastefully produced video, and you can’t pay your rent with the latest public relations photo-op. We are way, way past that point now. We need action and we need to make demands of the Scottish Government as well as opposing the Tories.

Last week I wrote:

“Independence supporters must have the capacity to properly assess the domestic performance of the SNP at any time. But this is especially true if the party is also failing to deliver on independence and conditions for the Scottish working class are in a state of deterioration as price hikes hit.”

This is going to become more important in the months and years ahead. Last week we looked at the National Energy Company sell out:

“This was all to be set up for 2021. It sounded ideal then. Now? It could have played a central role in reckoning with the cost of living crisis. Not a mitigation, not a sticking plaster. Instead a solid piece of infrastructure, set up to directly benefit the Scottish people.”

This is just one of many initiatives that could be implemented to support workers and their communities. But confrontation with the system, and throwing out old certainties, are not going to be an optional extras if that is to be achieved.

I can’t underline this point enough: under no circumstances will the SNP leadership prosecute such a project in any serious way. Not against the power of the corporations, nor the power of the British state. Those interests are secured under the Scottish status-quo.

Even on relatively menial reforms we see very little.

We could scrap the unfair council tax, we could reverse funding cuts to local government, we could implement a proper industrial strategy. The National Care Service could actually be what those words suggest, and not yet another outsourced and privatised failure. We could bring in rent controls now and not wait until the end of 2025 - which is meaningless for those who are struggling to make ends meet in 2022.

The Scottish Government could have voted in favour of a windfall tax on energy companies. Yes - this is not a devolved issue. But why not build a platform to campaign around these matters? The answer is a simple: they don’t want to rock the boat.

The system is rigged. The radical energy of 2014 has been usurped. The questions now posed to Scotland’s working class majority cannot be deferred to the mirage of “indyref 2023” or to the lacklustre approach to policy in the here and now.

I would be interested in you fleshing out your reference to MMT? As far as I’m concerned people understanding the factual mechanics of the monetary system is the key to building pressure for the policy space this opens up. This is the way we recapture the state for our use not the 1%. Any details on your thinking would be appreciated.