This week I am joined by James Foley, author of a new book on the Scottish economy and nationalism. The Scottish Economy and Nationalism: Constructing Scotland's Imagined Economy is an academic study involving a number of important topics, which we attempt to break down in the following interview. James also co-authored Scotland After Britain: The Two Souls of Scottish Independence, which this newsletter has previously covered.

I hope you enjoy, and are challenged by, some of the points raised. As always, feedback and debate are welcome.

Jonathon Shafi (JS): James, thank you for speaking to Independence Captured. To kick off, can you give us an overview of your new book and its core themes?

James Foley (JF): The book started off as my PhD thesis at Edinburgh University. When I first started, it was originally going to be about how the question of financialization and the financial crisis after 2008 might impact the Scottish independence referendum, and become a central theme within it. At the time this seemed logical enough because Scotland's two largest world leading corporations, the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and HBOS, had suffered quite monumental collapses, which were of an almost global scale. RBS was one of the biggest banks in the world. So I wanted to examine how this would end up being refracted into Scottish politics. I started the PhD in the early days of the independence campaign. But what I found while doing the research was the questions related to the financial crisis were impacting in ways that I hadn't quite anticipated and expected. So as the PhD evolved it became more focussed on a series of interlocking issues which ended up dominating the 2014 campaign.

As I expected from the start the question of Scotland's economic capacity, and interrelated questions that were pragmatic and economic in nature, were central themes. But it also became an outpouring about other and more complex things to do with the agency of working-class people historically, the role of North Sea oil in measuring the size of the Scottish economy and the question of the European Union. So eventually what it became was a case study of what it means to "be" an economy, and how we might conceive of a specifically national economy as societies become more defined by the needs of international capitalism, and how globalisation can serve to constrain our ability to imagine what self-rule on an economic basis might look like.

So while I did also include a chapter on the financial crisis, and the various ways in which it was framed by unionists and nationalists during the independence campaign, I found that in order to try and think about the underlying problems there had to be an account of the multifarious ways in which the Scottish economy became contested in political terms since the 1970s.

JS: Can you unpack what you mean by an “imagined” economy in the book?

JF: The economy shapes what we do on an everyday basis, and you cannot float politics free from its various constraints. The book takes from a Marxist perspective concerning the relationship between social action and the economy. In other words, it was about the ways in which people might find their imagining of the future contoured by a status quo bias. That was quite an evident fact in 2014 for instance, where people tended to imagine that there was stability attached to belonging to the United Kingdom, partly because they took for granted that the way that things had operated in the past was the way that things would continue to operate for all time.

What many didn't foresee was the succession of inflection points that would come in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, which range from Brexit to the question of the climate, and from the coronavirus to the Liz Truss budget. But I also wanted to reflect upon the fact that the dominant imagination of the economic future might be something that people can challenge, and that this may form a basis for political action of a transformative nature. For example, I think you also saw in the 2014 campaign the emergence of a narrative from elements of the left in the Yes movement that Scotland could be something different economically, and that there was something fundamentally wrong with the way the economy had functioned for the past several generations under the settlement of the United Kingdom.

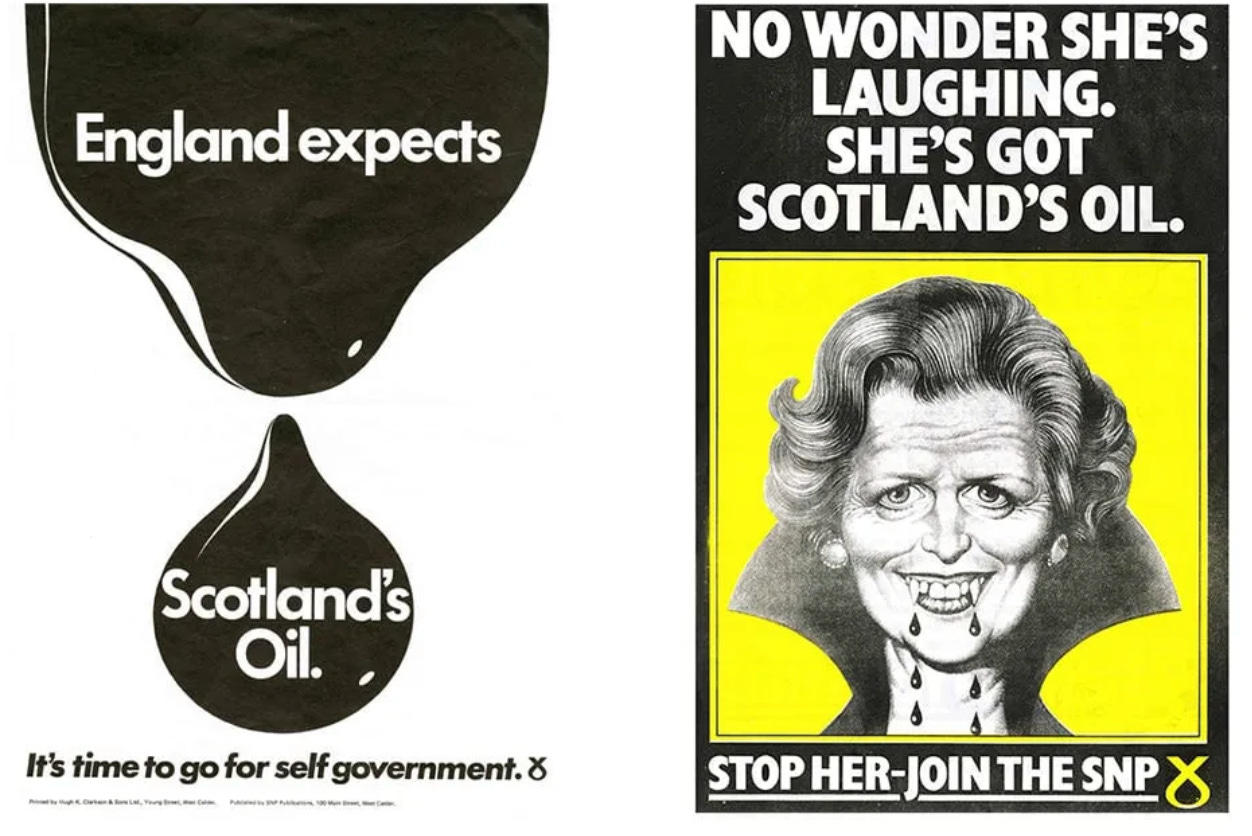

So although in many ways the economy constrains our actions, it is also true to say that major economic changes can provide new avenues for political action and contestation. For instance, the 1970s discovery of North Sea oil introduced all sorts of fascinating questions into Scottish political history. It's difficult to imagine the contemporary independence movement and the growth of the SNP without it. There's a cultural shift in what it means to be Scottish that is connected to this energy discovery.

At the same time the practical outcome of North Sea oil was the deindustrialisisation of large parts of Scotland because of the way it was utilised by Margaret Thatcher, and exposed Scotland to influences which were essentially the most buccaneering types of American individualist capitalism. So you can see the oil-based transformation in the Scottish economy in the 70s also helped to construct an imaginative frontier for what it meant to be Scottish. The whole cultural transformation of Scotland in the 70s and 80s can't be divorced from the developments around oil.

JS: It seems to me the discovery of North Sea oil had more cultural and political impact than Scotlan’s renewable potential. Thus far, at any rate. Is that a fair assessment?

JF: It's interesting. If you go back to the 1970s debate about North Sea oil, it wasn't just the SNP that was transformed by it. Even people who were unionists at the time changed the way they saw Scotland because previous to that it had been deemed as being economically dependent upon the United Kingdom. By contrast, when we discover North Sea oil, we can imagine a future where Scotland isn't just independent, but conceivably more economically advanced than the rest of the United Kingdom. That of course tends to be abaited by the fact that when it comes down to the political reality of it, the devolution referendum of the 70s failed.

Nonetheless, the initial impact was to create a whole new debate about what it meant to be Scottish, and what it meant to be working-class, and the SNP participated in that. But also, I think it transformed Scottish Labour and Scottish labourism and elements of the trade union movement. They saw a new foundation for working-class agency within Scotland that went beyond being politically cemented to a nationally organised British trade union movement, or to a labour movement which set out to achieve certain ends for Scotland within the United Kingdom. Today, however, there has been no renewed sense of agency introduced by the renewable energy debate whatsoever.

In many respects, the way the SNP and the Greens have handled the issue has tended to reinforce our reliance upon global capitalism and the various forces of economic liberalisation that have predominated for the last few decades. That in and of itself has precipitated a metamorphis of what it means to be “left-wing.” When North Sea oil was discovered, there was still the hope and anticipation that working-class people could achieve economic self-rule and overthrow the conditions of alienation in their workplaces. Those dynamics don’t feature in the same way at the present moment.

Partly this has to do with the fact that people just don't have confidence in the working-class as a historical agent anymore, and part of it has to do with the nature of renewables, because the industry is not creating new jobs at scale. Many of the jobs, for example, are offshored. Nothing about the way the "renewables revolution" in Scotland has been conducted has served to empower working-class people, nor has it been much of a debate within the left. Certainly not within modern Scottish nationalism, the SNP leadership, and the Scottish Greens.

JS: Over recent years the SNP have prioritised their opposition to Brexit, largely on the basis of its disruption to free markets, as a central plank of their independence case. That surely raises something of a contradiction, since Scottish independence which delivers economic autonomy must entail similar forms of friction?

JF: Firstly we should note the irony of the fact that one of the reasons that people may have chosen to remain within the United Kingdom back in 2014 was the reassurance of accessing the European Union. That was one of the key points put across by the Better Together coalition, Alisdair Darling and so on. But also I would say if you look at what has transpired since then, the whole idea of independence has become little more than about the question of how we access the markets of the European Union.

There are a number of contradictions here. If your priority is market access on standard neoliberal grounds, as it does indeed appear to be for many people on the left nowadays, then clearly the status quo of the union is the better immediate option insofar as it guarantees access to the UK "single market" which is a much larger economic partner in the current climate for the Scottish economy.

So in terms of sheer market access, the logical thing to do if that is your only priority, is to retain the UK union in its current terms, maybe with some tweaking here or there. There's not a coherent market-based account of why you should want Scottish independence in the first place. Yet that remains the central argument put forward by the SNP leadership. But a further issue is there has never been a coherent account of why replacing one form of undemocratic control over Scotland's resources for another would be any better. Clearly, there are huge problems with the UK Union in its current form. Nonetheless, those limitations also exist within the European Union, and for various reasons we probably have more possibility of democratic control within the United Kingdom than we would have within the European Union.

Now, I don't think that in any way invalidates the case for Scottish independence. It doesn't even mean to say that you can't make the case for Scotland to be a member of the European Union. But I think it does mean that philosophically the case for Scottish independence has been thoroughly distorted. The worrying thing is how little this has troubled the leadership of the SNP or pro-independence intellectuals in Scotland. They don't seem to want to examine the contradictions in their own case and are quite happy to dine out on the fact that there's a majority of people in Scotland who dislike the Conservatives or Brexit on a broadly cultural level, without doing the required programmatic work which I think would be necessary to achieve independence. In many ways, regardless of your view on the constitution, there has been a myth built up around Scotland and the European Union in recent years that perpetuartes paralysis in the political system.

JS: Lastly, in your book, you talk about the relationship between devolution and the neoliberal economic model. After 25 years, how do you assess the degree of social progress, or otherwise, as it relates to decision-making in Holyrood?

JF: If you go back to the origins of where devolution came from, the grievance behind it was often based on what Margaret Thatcher was doing to industries, communities and jobs in Scotland. With so little political legitimacy to carry out this programme at the time, it inspired a lot of resistance. That said, this gradually fused into a consensus around the idea that if we had a settlement around devolution, then Thatcherite policies would never come to be implemented against Scotland's will in the future. But the devolution settlement that we got in the late 1990s, was established at a time when there was a mood of triumphalism about American-led globalisation, free markets and so forth. So all of the economic things that Margaret Thatcher had done to Scotland, broadly speaking, were now implanted within the policy agenda of New Labour.

At best, I think what Labour did was to try and combine that type of support for free markets and privatisation with a supplementary redistribution of resources from the centre in order to try and alleviate some of the underlying problems around power, poverty and class inequality. Nonetheless, the actual impact of New Labour governance was the vastly increasing wealth of the 1%. While Scotland ended up with a devolved parliament, completely dominated by the centre-left in various guises, transformative change on class inequality was almost nil.

In retrospect you can look at it and say, well, it wasn't the fault of the parliament, because economic forces now are so overwhelming that political power is completely impervious to them. So all we can do is have a few policy changes here and there because the economy is essentially untouchable, and we cannot blame politicians for the way that our economic settlement works. But my attitude was more critical. The way in which states have been transformed by the neoliberal consensus has meant that, in general, it is the case that politicians are insulated from popular pressure and popular accountability. The European Union is broadly symptomatic of that. Far from taking power away from politicians at the national level, its real effect has been to empower politicians and domestic elites to be able to resist demands from the population for progressive transformation on the front that has anything to do with the economy.

Arguably, devolution works in a very similar way and has transpired, particularly in the last decade or so, to be a very effective mechanism for channelling politics away from questions of social class and towards questions of nationhood. To be quite blunt about this, half the population blame the Tories and half the population blame the Scottish nationalists who are in power. You can blame that on the population, or you can blame it on cynical politicians if you like. But actually, the deeper cause of many of those things is the way in which states were reordered on the basis of multilevel governance.

The point of Scottish independence is to challenge that and to rebuild a culture which implies some degree of centralisation, where we can think about the possibility of economic self-rule as a means to starting the process of being able to hold political elites accountable for what is happening in relation to economic policy. We have simply been unable to do that. If you look at the crises that global capitalism is throwing up for us today, we have to be able to challenge the way in which citizens and states interact.

Whether it's the transnational institutions and transnational corporations that have dominated over the last period, or whether it's things like the devolved settlement and the confusion over where your real power lies, I think the goal of a coherent independence movement is for democratic control and accountability as the foundation of self-rule at the level of citizens.

Infrastructure (aka investment) question - oil in north sea inherently global due to investment required on a per rig basis. Renewables are local in terms of infrastructure enabling local control/democratic accountability. The 'working class' organised to mirror the pattern of capital investment...??? lol (interconnectors and transmission networks 'national' not global and easily covered by local contributions)

That’s interesting. I think the sympathy with the European project is more than about access to markets. It’s much more than that. It’s about working together on things like food security, environment, climate. The four freedoms are a huge source of opportunity too. And Scots look over at Ireland- historically the UK has ben able to bully Ireland mercilessly but its EU membership has put it much more on an equal footing.